(This story originally appeared on W42ST, the magazine of Hell’s Kitchen, on July 11, 2020.)

The City That Never Sleeps was in bed early the night I arrived.

But each day since then I’ve had the pleasure of watching my new neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen wake up bit by bit, one little human interaction at a time. These images, these experiences, give me hope for Hell’s Kitchen. They give me hope for humanity.

That first night here in Manhattan was June 1. An 11 p.m. curfew – the first curfew in New York City since World War II – followed immediately by an 8 p.m. curfew the rest of the week, as violent riots gripped the city and businesses here in Hell’s Kitchen and beyond were boarded up and even vandalized a block or two from my apartment.

And then there was something about a pandemic. A human tragedy, of course. A tragedy accompanied by devastating economic, social and psychological consequences.

Bars and restaurants closed. Crowds discouraged. No schools. No games. No theater. No concerts. Human interaction shunned. People on edge. Political divides deepened. Some people afraid still to even walk by other human beings.

Basically, everything that makes Manhattan magical – the food, the drink, the entertainment, the crowds, the street life, the chaos, the tourists, the fearless celebration of life amid a teeming pool of humanity from all corners of the globe – all of it in limbo.

Not the way you envision arriving in New York, braving the bright lights of the big city in a blaze of boastful Big Apple braggadocio.

“Here I am, Gotham!”

Oh, and one other thing: it’d be 10 days before I had internet or cable TV connected. It was almost like stepping back in time.

So I spent my first week or so in Hell’s Kitchen exploring by foot or by bicycle what little was open in the neighborhood and beyond by day, then heading home before curfew in still broad daylight while riding out the evening alone putting away my boxes of books and surfing the internet via iPhone hotspot.

But I knew what I was getting into before I left Boston. Of course I knew. We were going through the same thing back there – just not quite to the same degree.

But you know what? I wasn’t worried about any of it. Certainly not afraid. Hopeful instead. Always hopeful. Happy to be here. Arriving in Manhattan at its lowest hour will someday make a great life story. I bet on the Big Apple at a time when it was bleeding.

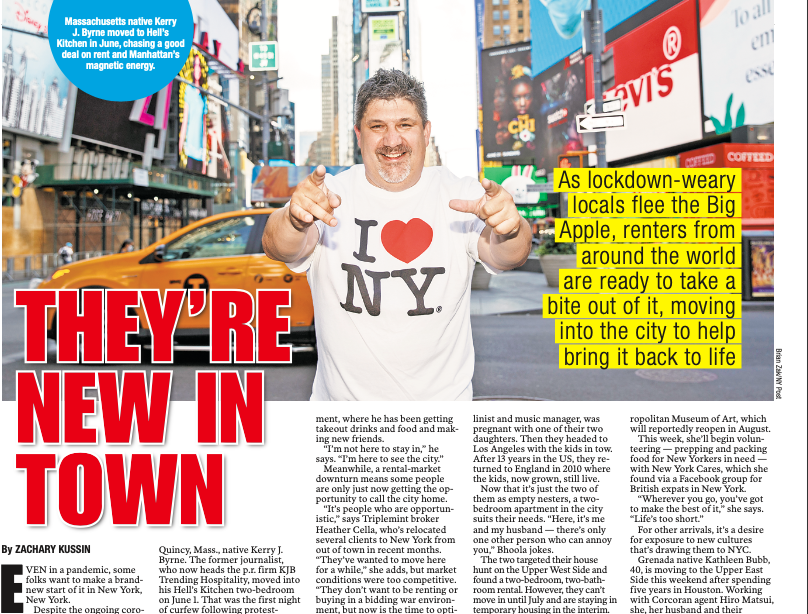

The New York Post even wrote about my arrival with a full-page spread just two weeks after I landed. I think the editors welcomed the idea of some positive news after a few months of nothing but negativity.

I’d been in love with New York City since I was a teenage boy, studying each night the National Geographic map of Manhattan that hung next to my bed; amazed every time its majestic skyline appeared on a movie screen; thrilled to visit for the first time in 1988 after meeting a fellow Boston College freshman buddy from Bayonne, N.J., feeling like I already knew every neighborhood in town, carrying maybe $10 or $20 in my pocket, but every sense alive amid the miracle of Manhattan.

We’d buy $1 beers at the bodegas and drink them out of brown paper bags walking around town; cheer the heated street ball battles in the hoop courts of Greenwich Village; sneak into the bars of Bleecker or Christopher streets with our fake IDs; ride the glass elevators at the Marriott Marquis in Times Square as if they were a free amusement park attraction (long before 9/11 when anybody could just walk into the lobby); play the street-hustler shell games or try to score a couple joints on 42nd Street when it was still a seedy den of hookers, grifters and drug dealers; window shop on 5th Avenue for treasures well beyond our means; spend our last few dollars at the strip clubs and peep shows on 8th Avenue here in Hell’s Kitchen; toast John Lennon’s memory at The Dakota on West 72nd.

One time at 19 years old I was dismissed from the hospital after appendix surgery with staples in my stomach and pain killers in my system and immediately made my friends Frankie C. and Fo Man drive with me to Manhattan at 2 a.m. We returned to Boston 24 hours later after a glorious sleepless tour of the city, all the way from Wall Street to the Upper West Side, almost all of it on foot. My mom and my doctor were furious. I was elated.

I’ve been to Manhattan hundreds of times since, each time filled with that same sense of boyhood wonder, awed by its beauty, its size, its diversity, its chaos, typically staying right here in Times Square or Hell’s Kitchen. A Midtown kind of guy. So this is where I wanted to be and as luck would have it this is where I landed.

Here’s why I arrived here in the midst of riot, pandemic and economic catastrophe: to watch the world’s greatest city rebound and return to its former glory, to hopefully be a part of its revival.

Slowly but surely, it’s happening. Each day a little better, a little busier, a bit more normal than the day before.

It’s the little things that capture my attention and give me hope.

The first sign of better days ahead for me was watching a grey-haired man with a long pole in his hand, unraveling the wind-whipped flags that hung above the entrance of McQuaid’s Pub on 11th Avenue one morning in early June, maybe my first or second or morning here.

Being a good Boston Irishman, I knew the flags out front: the U.S. and the Republic of Ireland, of course, along with those of the Irish counties of Monaghan and Donegal.

I went over to say hi. His name was Tom McQuaid. He’s owned Irish pubs in Manhattan for more than 50 years, this one on 11th Avenue since the 1990s. He had shut down two years ago for a major remodeling effort and planned to open in time for St. Patrick’s Day. Then the restaurant shutdown came in early March. He had been open for take-out service only for maybe a couple weeks.

But the obvious concern he had over the state of his flags following the worst crisis of his life as a publican filled me with a certain sense of joy. The little things still mattered.

Turns out the bartender, Big Timmy, was from County Kerry. He didn’t believe my name was Kerry. No Irishman does. It’s really an Irish-American name – and an Irish-American female name. So he busted my balls and I busted his and within a day or two of arriving I had found my new local hangout.

I’ve since cultivated new crowd of friends, most of whom had just met after emerging from their homes for a few drinks at McQuaid’s following the Covid quarantine. We visit each other’s roof decks and marvel at the expanse of the city after months of being shut in at home, tour the bars and restaurants of the neighborhood, and even vacationed together in Narragansett, R.I. 4th of July weekend.

Before leaving Boston I had joined a Hell’s Kitchen Facebook page. I’ve met several people through the page. One of them, Nikki, is native of Jamaica who served in the U.S. Air Force. Her husband Adam is Jewish. Their buddy Hassan is a Pakistani immigrant. We met for drinks one of my first nights here at the Landmark Tavern and several times since.

Somewhere in there is a joke: an Irish-Croatian-Native American, a Jamaican U.S. Air Force veteran, a New York Jew and a Pakistani immigrant walk into a bar … I don’t have a punchline, really. But the diversity of the neighborhood, of the city, remains encouraging.

I’ve met the Turkish owner of The Jolly Goat, a great little coffee shop on West 47th with excellent espresso and a collection of antique Ottoman Era coffee cups; had my first New York haircut from Kazakhstani barber Erik on 10th Avenue; met a Colombian guy named Juan Carlos at Romeo & Juliet coffee shop on 42nd Street and spent two hours talking to him about his theory that baseball is a metaphor for American life, while a reporter from Univision walked by to file a video with the two of us in the background.

I’ve enjoyed dumplings made by the mother of my new buddy Eddie, a first-generation Chinese-American who lives in Hell’s Kitchen but grew up in Queens; savored some delicious handmade banger sausage delivered by one of the bartenders at McQuaid’s from his favorite Irish butcher in the Bronx; and experienced global flavors at the neighborhood’s restaurants now that they’re open for outdoor seating.

The most uplifting moment of my first five or six weeks involved something as simple as sidewalk dirt.

It had to be June 2 or 3. Most everything still shutdown. Virtually no traffic on the West Side Highway. I was walking south down the highway and there was an elderly black man out there with a pole with a small steel two-pronged fork at the end.

He was dutifully scraping up all the dirt in the cracks between the concrete slabs of the sidewalk and then hosing off the dirt.

I was struck by the image of this old man amid the incomprehensible immensity of the Manhattan skyline, dutifully cleaning up the dirt on the sidewalk in this tiny little corner of the big city. It filled my heart with joy. It reminded me of something I read once about the Pilgrims traveling across the immensity of the Atlantic Ocean in a little wooden boat, buoyed only by faith and hope in the future.

There is hope for Hell’s Kitchen, there is hope for all us, there is a bright future ahead, as long as there are people willing to clean up the sidewalks, unfurl the wind-whipped flags and make new friends from new towns and other nations – everyone doing their part to make the city a better place, no matter how humble the chore. I hope to contribute in some little way.